By Dr. Hasina Akhter

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin B6 is one of the nine water soluble B vitamins. It is also known as pyridoxine (3-hydroxy-4, 5-dihydroxy-methyl-2-methylpyridine). Pyridoxal-5’-phosphate (PLP) is the coenzyme form of this vitamin that plays a vital role in more than 100 enzymatic reactions involved in amino acid and protein synthesis as well as fatty acids and carbohydrates metabolism (1–2).

Vitamin B6 is one of the nine water soluble B vitamins. It is also known as pyridoxine (3-hydroxy-4, 5-dihydroxy-methyl-2-methylpyridine). Pyridoxal-5’-phosphate (PLP) is the coenzyme form of this vitamin that plays a vital role in more than 100 enzymatic reactions involved in amino acid and protein synthesis as well as fatty acids and carbohydrates metabolism (1–2).

DISCOVERY

In 1930, Peters and colleagues first reported “rat acrodynia”, a disease where rats suffer from severe skin injury. Four years later in 1934, Gyorgy discovered vitamin B6 as an effective factor to treat this disease (3–4).Thereafter it was isolated in crystalline form by Lepkovsky in 1938 (5). In the following year, Harris and Folkers, and Kuhn and his associates separately showed vitamin B6 as a pyridine derivative (6,7,8).

STRUCTURE

The structure of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine and PLP) are given below:

Pyridoxine

Pyridoxal-5’-phosphate (PLP)

Other than pyridoxine and PLP, five more isoforms of this vitamin are pyridoxal, pyridoxine 5’-phosphate (PNP), pyridoxamine (PM), pyridoxamine-5’-phosphate (PMP) and 4-pyridoxic acid (PA).

DIETARY SOURCES (9–12)

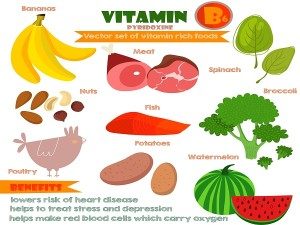

Major dietary sources of vitamin B6 are chicken, beef liver, fish (Tuna, Herring, Trout, Salmon), whole grain foods, nuts, potatoes, sweet potatoes, spinach, avocado, brewer’s yeast and some non-citrus fruits such as banana, watermelon etc. Fortified cereals and breads may also contain this vitamin.

RECOMMENDED DIETARY ALLOWANCES [RDAs (mg/day) FOR VITAMIN B6 (9]

| AGE | MALE | FEMALE | PREGNANCY | LACTATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-6 months | 0.1 mg/day | 0.1 mg/day | ||

| 7-12 months | 0.3 mg/day | 0.3 mg/day | ||

| 1-3 years | 0.5 mg/day | 0.5 mg/day | ||

| 4-8 years | 0.6 mg/day | 0.6 mg/day | ||

| 9-13 years | 1.0 mg/day | 1.0 mg/day | ||

| 14-18 years | 1.3 mg/day | 1.2 mg/day | 1.9 mg/day | 2.0 mg/day |

| 19-50 years | 1.3 mg/day | 1.3 mg/day | 1.9 mg/day | 2.0 mg/day |

| 51+ | 1.7 mg/day | 1.5 mg/day |

WHO ARE AT RISK FOR VITAMIN B6 DEFICIENCY

-

Severe deficiency of vitamin B6 is uncommon. However, alcoholics are at high risk due to poor dietary intake associated with impaired metabolism of this vitamin (9).

-

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and other malabsorptive autoimmune disorders appear to have low plasma PLP concentrations [13].

-

Patients with chronic kidney diseases or have undergone kidney transplant show vitamin B6 deficiency (13, 14).

FUNCTIONS

[9,11]-

In its coenzyme form (PLP), vitamin B6 is involved in the metabolism of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates as well as synthesis of amino acids and hemoglobin, the vital constituent of blood.

-

Vitamin B6 (PLP) also participates in glycogenolysis, the release of glucose from the stored glycogen in the body as well as gluconeogenesis, the synthesis of glucose from amino acids.

-

It also promotes the production of signaling protein of the immune system (i.e. interleukin-2) as well as immune cells (i.e. lymphocytes).

-

Vitamin B6 (PLP) also participates in the synthesis of nucleic acids.

-

There is an association between elevated levels of homocysteine in the blood and dementia. Vitamin B6 together with B12 and folic acid help maintaining normal levels of homocysteine in the blood as well as synthesis of neurotransmitters such as GABA (gamma amino butyric acid), dopamine, and serotonin. Thus it has a role in cognitive function.

DEFICIENCY OF VITAMIN B6

-

Abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns, microcytic anemia, and poor immune functions have been reported in vitamin B6-deficient adults (9–10).

-

Severe vitamin B6 deficiency may cause neurological problems such as irritability, depression, and confusion. Moreover, inflammation of the tongue, sores or ulcers of the mouth, and ulcers of the skin at the corners of the mouth are additional symptoms

(15).

-

Infants suffer from irritability, convulsive seizures and abnormally acute hearing due to vitamin B6 deficiency (10).

TOXICITY

Although vitamin B6 is a water-soluble vitamin and is excreted in the urine, long-term supplementation with high doses of pyridoxine (> 1000mg/day) may cause sensory neuropathy, a condition characterized by pain and numbness of the extremities followed by difficulty in walking (16–19). Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and heart burn are also reported due to excessive vitamin B6 intake (16). To prevent supplementation overdose, the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine has set the tolerable upper intake level for pyridoxine at 100 mg/day for adults 9.

VITAMIN B6 AND HEALTH

Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy

About half of the pregnant women experience “morning sickness” characterized by frequent occurrence of nausea and vomiting in the first few months of pregnancy [20–21]. This condition usually lasts throughout the day and can disrupt a woman’s daily functioning. Vitamin B6 at a dose of 10–25 mg three or four times a day is recommended by American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) to treat this condition [22].

Cognitive function and Alzheimer’s disease

An association between vitamin B6 and better memory test scores in men aged 54–81 years was reported before [23].Moreover, a systematic review of 14 randomized controlled trials found insufficient evidence of an effect of vitamin B6 supplements alone or with vitamin B12 and folic acid on cognitive function in people with normal cognitive function [24].

A recent placebo-controlled trial found that a daily B-vitamin supplementation (B12, B6 and folic acid) that led to significant homocysteine lowering in high-risk elderly individuals could limit the progressive atrophy of gray matter brain regions associated with the Alzheimer’s disease (25). Because of mixed findings, more research is needed to see whether vitamin B supplements may blunt cognitive decline in elderly people.

Cardiovascular diseases

Elevated levels of homocysteine has been identified as a potential risk factor for cardiovascular disease (26-28). Vitamin B6 together with folate and vitamin B12 are involved in homocysteine metabolism and thus might reduce cardiovascular disease risk by lowering homocysteine levels. However, the research to date provides inadequate evidence that vitamin B6, alone or with folic acid and vitamin B12, can help reduce the risk or severity of cardiovascular disease and stroke.

Premenstrual syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) are symptoms, including but not limited to fatigue, irritability, moodiness/depression, fluid retention, and breast tenderness. PMS appears after ovulation and go down with the onset of menstruation. A meta-analysis of nine published

trials involving almost 1,000 women with PMS found that vitamin B6 at doses up to 100 mg/day are likely to be beneficial in treating premenstrual symptoms and premenstrual depression. However most of the studies analyzed were small and several had methodological weaknesses [29]. Another study showed that 80 mg pyridoxine taken daily over the course of three cycles was associated with statistically significant reductions in a broad range of PMS symptoms, [30]. The effectiveness of vitamin B6 in removing the mood-related symptoms of PMS could be due to its role as a coenzyme in neurotransmitter (i.e. GABA, serotonin etc) synthesis [31]. More research is needed to draw any conclusive role of vitamin B6 in alleviating PMS.

| DRUGS | DRUGS USED FOR | INTERACTION |

|---|---|---|

| Birth control pills | Prevent unwanted conception | Reduce plasma PLP level

(Estrogen in pills may interfere with vitamin B6 metabolism) |

|

Long term use of NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) |

Prevent pain, inflammation | Impair vitamin B6 metabolism |

|

Isoniazid and cycloserine |

Tuberculosis | Reduce bioavailability of B6 |

|

L-Dopa |

Parkinson’s disease | Reduce bioavailability of B6 |

Moreover, large doses of vitamin B6 decrease the efficacy of two anticonvulsants, phenobarbital and phenytoin, and of L-Dopa [34, 19].

Refrences

-

Leklem JE. Vitamin B-6. In: Shils M, Olson JA, Shike M, Ross AC, eds. Nutrition in Health and Disease. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1999:413-422.

-

Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Vitamin B6. Dietary ref Intakes: Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press; 1998:150-195.

-

McCormick D. Vitamin B6. In: Bowman B, Russell R, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 9th ed. Washington, DC: International Life Sciences Institute; 2006.

-

Mackey A et al. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 10th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

-

National Nutrient Database for Standard ref, Release 26. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

-

Mackey A, et al. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 10th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

-

Merrill AH, Jr., Henderson JM. Diseases associated with defects in vitamin B6 metabolism or utilization. Annu Rev Nutr 1987; 7: 137-56.

-

Leklem JE. Vitamin B6. In: Machlin L, ed. Handbook of Vitamins. New York: Marcel Decker Inc; 1991:341-378.

-

Gdynia HJ et al. Severe sensorimotor neuropathy after intake of highest dosages of vitamin B6. Neuromuscul Disord 2008; 18: 156-8.

-

Perry TA et al. Pyridoxine-induced toxicity in rats: a stereological quantification of the sensory neuropathy. Exp Neurol 2004; 190: 133-44.

-

Matthews A et al. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD007575.

-

ACOG (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology) Practice Bulletin: nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103: 803-14.

-

Riggs KM et al. Relations of vitamin B-12, vitamin B-6, folate, and homocysteine to cognitive performance in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Clin Nutr 1996; 63: 306-14.

-

Balk EM et al. Vitamin B6, B12, and folic acid supplementation and cognitive function: a systematic review of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:21-30.

-

Douaud G et al. Preventing Alzheimer’s disease-related gray matter atrophy by B-vitamin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110(23):9523-9528.

-

Schulz RJ. Homocysteine as a biomarker for cognitive dysfunction in the elderly. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2007;10: 718-23.

-

Refsum H et al. The Hordaland Homocysteine Study: a community-based study of homocysteine, its determinants, and associations with disease. J Nutr 2006;136(6 Suppl):1731S-40S.

-

American Heart Association Nutrition Committee, Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation 2006; 114: 82-96.

-

Wyatt KM et al. Efficacy of vitamin B-6 in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ 1999; 318: 1375-81.

-

Kashanian M et al. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) therapy for premenstrual syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007; 96: 43-4.

-

Bendich A. The potential for dietary supplements to reduce premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms. J Am Coll Nutr 2000; 19: 3-12.

-

Clayton PT. B6-responsive disorders: a model of vitamin dependency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006; 29(2-3):317-326.

-

Morris MS et al. Plasma pyridoxal 5′-phosphate in the US population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008; 87(5):1446-1454.

I in addition to my pals appeared to be going through the great tips found on your web site while at once got a terrible feeling I had not thanked the website owner for those techniques. All of the guys became totally glad to read through all of them and have simply been enjoying those things. Many thanks for turning out to be really helpful and also for picking out these kinds of useful areas millions of individuals are really desperate to know about. Our sincere apologies for not expressing gratitude to earlier.